Primer on GAN

A General Adversarial Network (GAN) is comprised of two models, a generator and a discriminator. Given a set of data, the generator network attempts to generate samples that would come from the same distribution as the data while the discriminator network attempts to distinguish between whether or not a given data point is from the distribution of the data or a fake created by the generator. In some sense, the models are "competeing" against each other during the training process. During training, the generator produces better fakes while the discriminator becomes more precise in identifying the fake from the real. This can be seen in the typical objective function for GAN. Given a generator, that maps from samples of gaussian noise to the output space of the real data, and a discriminator the objective function is

The goal is to minimize this loss over all possible and maximize this loss over all possible .

You can use GANs to generate fake examples in any data domain, from images to music to text. CycleGAN is trained specifically to generate image data.

CycleGAN

CycleGAN was introduced in a paper titled "Unpaired Image-to-Image Translation using Cycle-Consistent Adversarial Networks" [1]. Before this paper, Pix2Pix showed great results learning associations between two domains of images in settings where input and output were paired [2]. Paired data is often not available or requires a lot of manual work to label properly. CycleGAN is an approach to unpaired image translation using GANs. Instead of having a generator that maps from noise to a data distribution, we want to map data from one image domain to a different image domain . Instead of generating a fake image from random noise, the generator now aims to map a set of images in one domain to a set of images in another. For example, you could have a generator that takes a picture of a brown horse and returns a similar image of zebra. The zebra discriminator's job is to determine if a given image is a real zebra or a fake zebra.

CycleGAN uses two different GANs for the task of image translation. The model has two generators, and and two discriminators that identifies images in the domain and that identifies images in the domain. In addition to adding another GAN, CycleGAN also changes the standard loss function by adding cycle loss and identity loss. These additional losses are added to impose more structure to the generators. Cycle loss imposes the constraint that we want and where and are the identity for data in the domain and domain respectively. In other words, we want . This encourages the generators to not become permutation functions of the training data. This loss is given by

Identity loss imposes the constraint that if a generator is given an image in the domain it is mapping to, then the generator should return the same image, .

In the paper, identity loss was used only for the task of translating paintings to photos. Also, they noted that there was no difference to their results when they defined the cycle loss and identity loss using L2 norm vs L1 norm.

The architecture of the generator and the discriminator are made up of several convolutional layers. The generator has several downsampling convolutional layers, into several Resnet blocks, into several transposed convolutions. The discriminator is made up of primarily downsampling convolutional layers. The final prediction of the discriminator network is not a scalar, but a 30 x 30 output (assuming input images of 256 x 256). This output is compared against a target of a 30 x 30 tensor of 1's or 0's. The intpretation of this 30 x 30 output is that each entry in this tensor represents the discriminator's prediction of whether a certain patch of the input image is real or fake. This type of discriminator is called PatchGAN since the output evalulates patches of the input. The authors of CycleGAN have another paper where they introduce and talk about PatchGAN [2].

Model Results

I tested CycleGAN on two applications listed in the paper, style transfer and unpaired image translation, but using different datasets.

Style Transfer on MTG Lands

For style transfer, I wanted to transfer a particular artists style onto art from Magic: The Gathering. In the CycleGAN paper, the authors implement style transfer using art by Claude Monet. Monet's body of work is a great way to test style transfer since he has a distinctive impressionist style of painting. I downloaded a 300 image dataset of Monet's works from Kaggle [3]. Here are some examples of Monet's art.

Magic: The Gathering is a card game with over 10,000 unique cards printed since the game's initial launch in 1993. The card game boasts a wide array of card art depicting all sorts of things from monsters to magical equipments to spells. Lands are another type of card in Magic: The Gathering and they commonly feature artwork of landscapes. This makes it a good application of style transfer for Monet's landscape art.

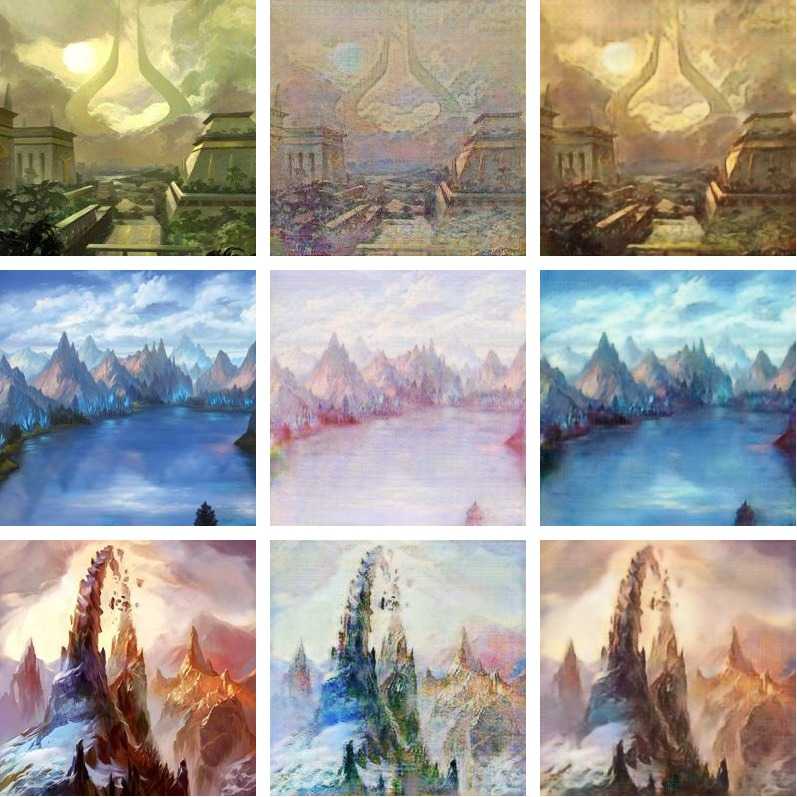

It took me around 16 hours to train the network for 200 epochs using training datasets containing 360 images of size 256 x 256 on a Nvidia RTX 2060 Super. Below are some of the results after training. The left column contains the original art from the card, the middle column shows the generator output mapping the Magic: The Gathering card to the Monet domain, and the right column shows the output of feeding the styled output into the other generator to send the image to the original domain.

The first thing that stands out about the style transfer is the way it changes the colors of the original art. The brighter and more vibrant colors are much more subdued in the style transfer result. This makes sense, as the body of Monet's paintings consists of muted colors. The generator mapping from Monet paintings to land art does a good job of recovering the original colors. The other thing that stands out is the attempt to apply the texture of a painting onto the land art. A lot of art used for lands are pieces that are photo-realistic digital art creations. It's interesting to see that CycleGAN learned to apply texture to the image in order to make it seem more like a painting than digital art.

Bald to Not Bald (RoGANe)

For unpaired image translation, I wanted to try something a bit more experimental. Many of the examples of unpaired image translation in the paper are on tasks that translate texture onto a given frame or shape (google maps and satellite image translation, UT Zappos50k edge and shoe translation, Yosemite summer and winter translation). I wanted to see how CycleGAN would for a task that required a more extreme translation. The task that I picked out was to see if CycleGAN could translate an image of a bald person to a person with hair and vice versa. Kaggle has an oddly specific dataset of over 200k images of bald and not bald people [4]. Due to the limitations of my machine, that's way more data than I can use to train CycleGAN in a reasonable amount of time. I used a very small subset of the data, 150 images of bald people and 150 images of not bald people, to train the model.

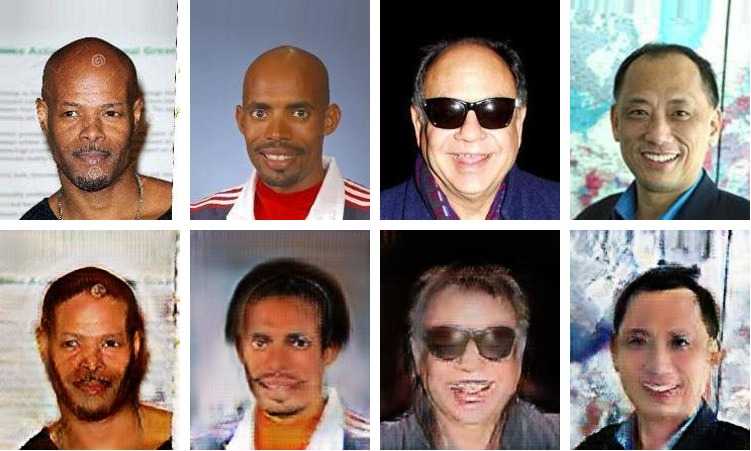

Below are some of the examples of the bald to not bald generator. I nicknamed this generator RoGANe after the men's hair growth product of a similar name. The top row contains the original images of bald people and the second row is RoGANe's attempt at translating the images to images of not bald people.

The quality of the results for bald to not bald image translation are a lot less consistent than the results I had for style transfer. This makes sense as the model was trained on less data and the task in some ways is harder. The generated images contain various blurs and artifacts and does not do a great job of retaining the features of the original image. However, the generator does learn the fundamental difference between the two domains, hair vs no hair. We see that in each case, the generated image has some kind of attempt to put hair onto a person that resembles the original.

Now going in the other direction. Below are the results of generator trained to do image translation from hair to bald.

Once again, the images have a lot of artifacts, but there is clear progress made in creating bald images! In the second column from the left, the generator even eliminates the gentleman's hat in the process. The two columns on the right are particularly interesting as well. Outside of the attempt to eliminate hair from the original images, the facial features of the output are more masculine than the input. This is a direct result of the distribution of the training data. The training data was formed by taking a random sample of the original dataset of 200k images. One thing about the dataset is that a majority of the images of bald people are men, and the majority of the images of people with hair are women. Even though the GAN was trained to map between the domains of bald and hair, it learned an unintended association due to the distribution of the training data. That is also why many of the output examples of RoGANe had longer hairstyles common to women.

Bias in Machine Learning

This is an example of how implicit biases can become incorporated in machine learning. Deep learning models have a lot more parameters which allow them to learn more complex associations between the training data and the target, but that comes at the cost of interpretability. It's hard to explain why a deep learning model returns a given output. Lack of explainability or improper training data can result in unintended biases in machine learining models. When these models are in production and generating predictions seen by millions of people, they could even be reinforcing those biases. It's important to remember that machine learning models learn associations in the data and the outputs can not directly be used to establish causal relationships. If you're interested in learning more about this topic, I highly recommend Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil [5].

In Conclusion

Since the original publication of the CycleGAN paper, there have been massive strides in the field of generative image modeling. StyleGAN2 from Nvidia produces scary good high definition images of fake people. It will be exciting keeping up with the latest GAN research. I had a lot of fun and learned a lot from implementing CycleGAN. You can find my PyTorch implementation of CycleGAN on Github. All credit goes to the original authors of this paper, Zhu, Jun-Yan and Park, Taesung and Isola, Phillip and Efros, Alexei A.

Links

[1] "Unpaird Image-to-Image Translation using Cycle-Consistent Adversarial Networks"

[2] "Image-to-Image Translation with Conditional Adversarial Networks"